Origins: How We Began

Women’s spirituality was in the air in the 1980s and 90s. There was a powerful upwelling of desire for change, as women who had been awakened by the women’s movement of the 1970s began to look in a new way at their own experience in all areas of life, including religion and spirituality. They were asking themselves new questions: What is sacred to us as women? As we reconnect with the sacred, how do we express and celebrate it? Some women worked within traditional religious institutions to try to bring about changes that would be more honoring to women, others left their churches and synagogues and created rituals and sacred circles of their own. They were joined by still others who had never felt an affinity with any institutional religion but found in this emerging field of women’s spirituality a place to reclaim and honor their own experience of the sacred and of spiritual life.

It was in this climate of awakening that what was to become the Women’s Well was born. Its first home was a center for holistic education in the Boston area, the Interface Foundation, where our original nine-month program, the Women’s Spirituality Program (WSP), was launched in 1994. The WSP included nine weekend workshops and weekly meetings, as well. This program was initially conceived of and designed by Susan Chiat, from Interface; Anne Yeomans, a psychotherapist and group facilitator; and Rose Thorne, a former director of Interface. Patricia Reis, a psychotherapist, teacher, and writer in Portland, Maine, also had considerable influence in shaping the original curriculum.

The program proved to be rich and transformative for both participants and facilitators alike. The faculty increased in number from one year to the next and the range of topics widened and deepened, addressing many aspects of women's spirituality. In 1998, after four exciting years at Interface, the three core faculty - Anne Yeomans, Patricia Reis, and Katy Szal, a Jungian analyst who joined Anne and Patricia in the second year - decided to make the big decision to leave Interface and continue the program on their own as the Women’s Well. Here are their stories.

THE FOUNDERS' STORIES

Anne Yeomans, co-founder and facilitator of the Women’s Well

I was a psychotherapist and group facilitator in the 1970s and 80s working in a field of psychology called Psychosynthesis, which was exploring the interface between psychology and spiritual life. I was not a stranger to spiritual experiences, or spiritual questions. But in the 1990s I discovered an emerging field called “women’s spirituality” and found a new context for reflecting on my own experience of the sacred as a woman.

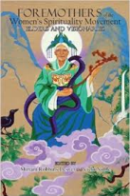

What brought me to women’s spirituality was reading. In some ways it seems strange, because so much of what happened was not based on books but on the experience of listening to my body, and trusting the truth of my own experience as a woman. Nonetheless, reading was what opened me to the ideas that were ultimately to become the foundation of the Women’s Well.  I am forever grateful to the women who wrote the first books on feminist spirituality and women’s spirituality. Their research, thinking, and writing changed my life (see, for example, Foremothers of the Women’s Spirituality Movement, Miriam Robbins Dexter and Vicki Noble, eds.).

I am forever grateful to the women who wrote the first books on feminist spirituality and women’s spirituality. Their research, thinking, and writing changed my life (see, for example, Foremothers of the Women’s Spirituality Movement, Miriam Robbins Dexter and Vicki Noble, eds.).

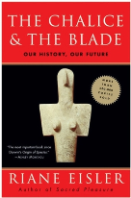

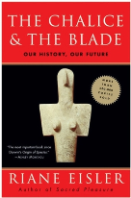

The first book I read in this field was The Chalice and the Blade, by Riane Eisler, which called attention to the very masculine-dominated world we live in, and the serious consequences for the future of humanity and the planet of continuing on in this way. She offered examples from pre-history of societies organized in what she called a partnership model where caring, compassion, and the life-giving qualities of relatedness were highly valued.

In her book Riane referred to the research of a woman I had never heard of before, but whose work was to become a guidepost and inspiration for me and for many others in the women’s spirituality movement. Her name was Marija Gimbutas. She was an archaeologist who had researched the Neolithic cultures of what she came to call Old Europe (6500-3500 BCE). Here she found evidence of social structures where people were living peacefully in egalitarian ways with each other, and in harmony with the Earth. These cultures were highly evolved artistically, and the Mother principle was honored and revered as sacred.

How did I come across Riane Eisler’s book? In the late 80s several friends recommended it, saying, “You must read this, Anne. You will love it.” I was walking past a bookstore in Santa Barbara, CA, with a friend, and we decided to go in and see if they had it. We entered the bookstore and a man who worked there came right up to us and said, “Are you looking for The Chalice and The Blade?” He pointed to a big stack of books at the front of the store. We looked at each other and laughed. We were “in the magic,” as we came to call it. And it was not the last time that something like this would happen.

How did I come across Riane Eisler’s book? In the late 80s several friends recommended it, saying, “You must read this, Anne. You will love it.” I was walking past a bookstore in Santa Barbara, CA, with a friend, and we decided to go in and see if they had it. We entered the bookstore and a man who worked there came right up to us and said, “Are you looking for The Chalice and The Blade?” He pointed to a big stack of books at the front of the store. We looked at each other and laughed. We were “in the magic,” as we came to call it. And it was not the last time that something like this would happen.

The next significant event for me was a trip to the former USSR in 1990, with a group of colleagues. We were going to be teaching Russian psychologists and therapists about Psychosynthesis, the spiritual psychology that we practiced in America. Disappointed not to be going to Moscow or St Petersburg, I was assigned to Lithuania, a country I knew nothing about.

We taught every afternoon, but in the mornings there was free time and my hosts asked me what kind of groups I wanted to meet in Vilnius. Nurses, politicians, musicians, teachers? I answered, “I would like to meet women.” “What kind of women?” they asked me. I answered, “Any kind of women.”

So the next day I was taken to the home of Lilija, a Lithuanian psychologist. There is much I can say about that morning, but at one point I was telling the group about women in America, and how we had been meeting in groups and talking to each other about our lives. I told them also about The Chalice and The Blade, and how the author was talking about ancient cultures which had honored women and the feminine. They were clearly very moved, and asked me if the book I was referring to had been written by Marija Gimbutas? I paused and said “No … but that name Marija Gimbutas seems familiar, and I think she was the archaeologist who researched those cultures I have been speaking to you about.” They said to me, did I know that Marija Gimbutas was Lithuanian, and that they were very proud of her! And also did I know that Lithuania was the last country in Europe to accept Christianity, and that for them the Earth is a goddess. The word for Earth was Žemė. The name of the goddess is Žemyna. I was stunned. Here was I in a country that I hadn’t wanted to come to, being given the next piece of a journey that I barely knew I was on.

I returned to the US with a wand traditionally carried at Easter in Lithuania that Lilija gave me to give to my mother. She showed me that it had the fronds for Christ at the top, and the flowers for the goddess all around the length.

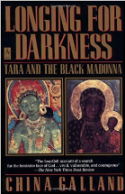

One book led to another. I remember particularly China Galland’s Longing for Darkness: Tara and the Black Madonna. China Galland had been raised Catholic, and in the book she writes of her search for the darkness in Catholicism and particularly for the Dark Mother. Another very important book for me was Elinor Gadon’s The Once and Future Goddess, where she chronicles the history of goddess worship going back to the Paleolithic era (35000-9000 BCE). She writes of the patriarchal takeover, and what she calls the “taming” of the goddess and her powers, and then in the final section of the book, she illustrates with pictures and words the reemergence of goddess consciousness through the art and drama of women today.

One book led to another. I remember particularly China Galland’s Longing for Darkness: Tara and the Black Madonna. China Galland had been raised Catholic, and in the book she writes of her search for the darkness in Catholicism and particularly for the Dark Mother. Another very important book for me was Elinor Gadon’s The Once and Future Goddess, where she chronicles the history of goddess worship going back to the Paleolithic era (35000-9000 BCE). She writes of the patriarchal takeover, and what she calls the “taming” of the goddess and her powers, and then in the final section of the book, she illustrates with pictures and words the reemergence of goddess consciousness through the art and drama of women today.

It all resonated so deeply with me, as if it were an articulation of a knowing I had always sensed, but never before had words or a context for. In the final section of her book, Elinor Gadon writes about the emergence of an Earth-based spirituality, the re-sacralization of sexuality, and the birth of Gaia consciousness - ecological wisdom for the renewal of life on this planet. As a peace activist and one who had studied and taught non-violence, reconciliation, and dialogue all through the 1980s, I was profoundly uplifted by her words.

It all resonated so deeply with me, as if it were an articulation of a knowing I had always sensed, but never before had words or a context for. In the final section of her book, Elinor Gadon writes about the emergence of an Earth-based spirituality, the re-sacralization of sexuality, and the birth of Gaia consciousness - ecological wisdom for the renewal of life on this planet. As a peace activist and one who had studied and taught non-violence, reconciliation, and dialogue all through the 1980s, I was profoundly uplifted by her words.

I saved the chapter on Mary, in Elinor Gadon’s book, for the last. It was in the middle of the book but somehow I knew it would be the most important for me, and indeed it was. As I read, I realized that Mary, whom I had always loved, was a goddess and belonged to the long and ancient history of earlier goddesses. Within Christianity she had become demoted, and domesticated, and had been severed from her body, her sexuality, and her roots in the ancient goddess tradition of which she was an expression.

I was alone in an old house in the country when I read all this, and quite spontaneously I was flooded with joy. I began to weep and to dance. Suddenly a sense of ritual emerged, and I felt like I was in the presence of something that was Big, Beautiful, Powerful, and Female, and that I was being asked to open to it. I was being asked to say “Yes” to it. “Here I am.” And so I did.

In many ways, I feel like all the rest came out of this one moment, and the commitment I made that day.

Soon after, I learned that Elinor Gadon was starting a doctoral program in women’s spirituality at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. I decided to go for three months and try it out. I flew to the West coast, enrolled in three graduate courses, and had a room of my own for the first time since I left my family of origin at twenty-one. Creative ideas began to come to me like birds that had been hovering and wanted to land. It felt like they had just been waiting for me to stop taking care of everyone else, and listen for my own voice.

After three months of study, I decided to leave the program and to return home. My marriage needed attention, and I convinced myself that this was not the right graduate program for me. Whether that was true or not, I will never know. I was leaving the doctoral program, but I knew I was not leaving my newly found passion for women’s spirituality, nor the commitment I had made that day in the country to an expression of the divine feminine. I didn’t know how the choice I made then would express itself next, but I was open and listening for what it wanted from me.

Before I left California I bought a drum from a woman in Santa Cruz, who was making drums that she wanted to put in the hands of women. She told me that I should dedicate my drum to some quality or energy. I decided that I would dedicate my drum to freedom. I remember well returning to my home in Concord, MA, at a time when no one else was in the house, and walking through every room on all three floors beating my “freedom drum.”

Not long after my return home, a woman named Rose Thorne, whom I had known as a former director of the Interface Foundation, a center for holistic education in the Boston area, called me. She was searching, too. Her children were now in school, and she was considering divinity school, but had been disappointed that none of the schools she was considering had courses in meditation at that time. Someone had said to her, “Anne Yeomans has just come back from a very interesting program in California, you should go and talk to her.” She listened to me tell the story of what had happened in California, and said to me, “ We can start this here. We can start this here at Interface.” I knew immediately, when she said this, that this was the next step I had been looking for.

In the fall of 1993 Rose Thorne, Susan Chiatt, who was on the staff of Interface, and I began to plan the curriculum for a nine-month program in women’s spirituality which would begin the next fall. It would meet in a workshop form for one weekend a month from September to May. It would also have one or two evening meetings each month.

By then I had met Patricia Reis, who had written Through the Goddess: A Woman’s Way of Healing. She was a colleague of Marija Gimbutas, and as an artist had done drawings for Marija’s books. Patricia was the one person I had heard of on the East Coast who was writing about this material that I had become so passionate about. She lived in Maine, and with my copy of her book with my notes and under-linings throughout, I drove up to see her.

Soon after my visit, I called her and asked if she wanted to teach in the new program we were creating, and she responded with an enthusiastic Yes, and faxed me topics for three weekends. The first was to be called “Reclaiming Our Sacred History,” which she wanted to teach with Joan Marler, a friend and colleague of hers who was an independent scholar in California. Joan had worked closely with Marija Gimbutas, as had Patricia. Patricia also proposed a weekend on women’s body stories, and another on female sexuality. And so the program unfolded with Patricia Reis playing a major part as a teacher and facilitator, and Joan Marler coming each fall to teach the work of Marija Gimbutas. Olivia Hoblitzelle, Prajna Hallstrom, and Katy Szal would soon join us, each of them bringing her considerable talents, experience, and wisdom to the course.

In the fall of 1994, the first nine-month Women’s Spirituality Program at Interface began with a group of 20 women. This first year was the beginning of what would ultimately come to be called the Women’s Well. It brought us all so much: new learnings, profound healing, a community of extraordinary women, and ultimately the courage to be braver about what was most important to each of us.

Patricia Reis, co-founder and facilitator of the Women’s Well

In the early 1990s I attended a conference put on by Harvard University called “Learning from Women.” During the afternoon break, I saw Elinor Gadon whom I knew from my days in the San Francisco Bay Area. She introduced me to her friend, Anne Yeomans. The rest is, as they say, herstory. There were phone calls back and forth and a pivotal visit. Anne was on fire with her vision of a Women’s Spirituality Program. I had just published Through the Goddess: A Woman’s Way of Healing. It was dedicated to the Neolithic archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, my teacher, mentor, friend, matchmaker.

It is hard to describe those days of revelation. I had moved from California to Maine in 1986 and had a psychotherapy practice at Women to Women in Yarmouth. While in California, I had studied, worked, and traveled with Marija Gimbutas, and was part of a very large coterie of women who were drawn to her discoveries of the Neolithic Goddesses and their Old European cultures. Marija’s work had been taken up by so many women for so many different reasons: her discoveries gave evidence of a time that honored, revered, and worshipped female power in all its multiplicity; a whole movement of women’s spirituality was formed around these discoveries; the work of artists, musicians, and poets flourished; academically trained women took on the formidable task of reinforcing the evidence for a culture that did not have war at its center, where the female body and women’s wisdom was celebrated. As Anne Yeomans says, there was a great fluorescence of study, retreats, workshops, and books - so many books - on the impact of Marija’s discoveries on contemporary culture. This was the ground out of which the Women’s Spirituality Program was born.

It is hard to describe those days of revelation. I had moved from California to Maine in 1986 and had a psychotherapy practice at Women to Women in Yarmouth. While in California, I had studied, worked, and traveled with Marija Gimbutas, and was part of a very large coterie of women who were drawn to her discoveries of the Neolithic Goddesses and their Old European cultures. Marija’s work had been taken up by so many women for so many different reasons: her discoveries gave evidence of a time that honored, revered, and worshipped female power in all its multiplicity; a whole movement of women’s spirituality was formed around these discoveries; the work of artists, musicians, and poets flourished; academically trained women took on the formidable task of reinforcing the evidence for a culture that did not have war at its center, where the female body and women’s wisdom was celebrated. As Anne Yeomans says, there was a great fluorescence of study, retreats, workshops, and books - so many books - on the impact of Marija’s discoveries on contemporary culture. This was the ground out of which the Women’s Spirituality Program was born.

The creative force that was present at this birth was exhilarating. Planning meetings at Anne’s home in Concord were filled with intensity, possibility, and guidance. Doors opened for us, both outer and inner, wonderful women responded to our call for teachers, courageous and eager women responded to our call for participants in a nine-month-long intensive program called the Women’s Spirituality Program. The learning community of Interface was the first home for the program we developed. Later, after we moved out of Interface, we renamed our program the Women’s Well.

Each Fall a core group of facilitators would meet and craft the nine-month-long program. Anne would say I built the spine. I was eager to share what I had learned and was learning. I always began each new group with my slide show, "A Woman Artist’s Journey," a multi-layered story of my artistic process while pursuing an MFA at UCLA and simultaneously opening to goddess mythology and images which informed a kind of female initiation. My teaching drew on my creative interests, art, visual images, books, literature. Each topic was alive for me. Fathers and Daughters; Mothers and Daughters; Sexuality, Spirituality, and Creativity; Women, Work, and Money; Reclaiming the Erotic; the Body Story. This work was clearly not for sissies! It required a great deal of courage for each woman who had signed up for this program. We were all helped by the energy, devotion, and dare I say, hunger of each group that gathered every Fall.

Each weekend I taught, I came armed with a large roll of white butcher paper and a big bag of colored markers. My weekends were always a mix of story and image as women worked on large body drawings, or genealogical maps of how work and money flowed through the parental lineages. For instance, for the Sexuality, Spirituality, and Creativity weekend, I asked the group to look at the way these three aspects of our being have lived different and separate lives. I asked, “What have you been able to live into? To show to the world? What has had to remain hidden?” I asked them to divide a long piece of paper into the three parts and notice the places that were blocked, silenced, inhibited, and where there had been some overlap. Then I asked them to make a new drawing - an “as if” drawing - where their sexuality, spirituality, and creativity could be integrated and to see and feel what that would be like. Sometimes, like in Recovering Aphrodite, we brought large colorful scarves and moved our bodies in tune with what we were discovering.

We always built an altar in the center of our space, a beautiful collection of images and artifacts that reflected the work we were entering.

One time, after we moved from Interface, we rented a space in an old stone church. We were not given the room we had signed up for and instead were expected to do our weekend in the actual church with its sanctuary! The weekend was on Body and Soul! We protested and were given another gathering space that let us spread out. How deeply ironic that we were attempting to write a new body story for women in the very place where women’s bodies had been thought of as dangerous if not downright evil!

Synchronicities like this often happened as we did the work of reclaiming women’s spirituality. The focus and intention of a group of women bent on recovering their authenticity generated a powerful force field. Pain, fear, sorrow, and grief gave way to release, energy, old passions, and joy. We did not believe in doing a spiritual bypass on any of it. It was exhausting and exhilarating.

Part of the beauty of the work for me was the working principle that the leaders were also participants. I did my own body maps - the wounded body, the healed body - I did a map of my own story with work and money. As leaders, we stretched ourselves and did everything we were asking our group to do. After each weekend, we facilitators often debriefed over a sumptuous dinner of sushi.

Needless to say, this work was transformative for both leaders and participants. One of the beautiful experiences for me was how we, as facilitators, developed our deep trust in each other and in the unfolding process. There was fear sometimes, doubt, even anger, but ultimately, we grew to trust not only the process that we had initiated but also the women who had so courageously entered into the process with us.

Katy Szal, co-founder and facilitator of the Women’s Well

Katy Szal (1945-2004) was one of the three co-founders of the Women’s Well. She knew of the nine-month Women’s Spirituality Program, forerunner to the Women’s Well, from her long friendship with Anne Yeomans. The two had been neighbors in the coastal town of Westport, MA, where Katy lived, worked as a potter, gardened, and raised her daughter Amma. Anne came there with her family in the summers and joined Katy in many family and community events. At some point over the years they discovered that they had a shared interest in images and artifacts from pre-history, particularly those that honored women and the feminine.

During the years when both women had young families, Katy owned a successful pottery studio, Suntree Pottery, and made grey and blue pots and lamps that she sold at craft fairs around New England and in museum catalogues. She was a potter for twenty-five years, exhibiting in museums and galleries across the United States. During this time she also helped dismantle and reconstruct a post-and-beam house, originally built in 1680, and surrounded it with flowers and vegetable gardens. She was a master gardener and also a great cook.

During the years when both women had young families, Katy owned a successful pottery studio, Suntree Pottery, and made grey and blue pots and lamps that she sold at craft fairs around New England and in museum catalogues. She was a potter for twenty-five years, exhibiting in museums and galleries across the United States. During this time she also helped dismantle and reconstruct a post-and-beam house, originally built in 1680, and surrounded it with flowers and vegetable gardens. She was a master gardener and also a great cook.

In her forties, Katy initiated a major life change. She decided to focus on pursuing her lifelong interest in dreams and the guidance they offer. While still running her pottery business in Westport she embarked on a Master’s program in Counseling Psychology at the Pacifica Graduate Institute in Santa Barbara. After a summer program at the C.G. Jung Institute - Zurich, she made a leap of faith, closed the pottery studio, and moved to Zurich to pursue her dream of becoming a Jungian analyst. During that time, even though she was geographically far away, she followed the progress of the Women’s Spirituality Program closely, and sent Anne encouraging notes from Europe.

While in Switzerland studying Jungian psychology, she took numerous trips to the area of the Dordogne River in southern France, where she explored sites and caves where ancient artifacts had been discovered. She was determined to find the site where the Goddess of Laussel (20000 BCE) had been originally found. She knew this sculpture was discovered near the entrance to a cave near the Dordogne River where she and others believed ceremonies and rituals had been performed in ancient times. She spent several nights camping in that area at the time of the full moon, believing that our ancestors would have carved this image of the goddess in a place where the rising moon would have shone on it. She eventually identified the area where she thought it would most likely have been; she later took Anne there.

In December of 1994, Anne and Katy, pursuing their growing shared interest in the artifacts of pre-history, met up for a long weekend in Wiesbaden, Germany, to attend an art exhibit entitled “From The Language of the Goddess,” which explored the work of Marija Gimbutas. In the summer of 1995, they again traveled together in the Dordogne region of France where many of these ancient artifacts had been found.

After Katy completed her course work in Zurich, she returned to Massachusetts to write her thesis and was invited to join the Women’s Spirituality Program as a co-facilitator, starting in the fall of 1995. Katy brought to the Women’s Spirituality Program a lifelong passionate interest in archeology and the intimations it offers about the lives and priorities of our forbears. This interest had begun during her childhood in Arizona, where she had an uncanny knack for finding shards of pottery and spotting rock art and other evidence of people from earlier times.

After Katy completed her course work in Zurich, she returned to Massachusetts to write her thesis and was invited to join the Women’s Spirituality Program as a co-facilitator, starting in the fall of 1995. Katy brought to the Women’s Spirituality Program a lifelong passionate interest in archeology and the intimations it offers about the lives and priorities of our forbears. This interest had begun during her childhood in Arizona, where she had an uncanny knack for finding shards of pottery and spotting rock art and other evidence of people from earlier times.

Katy also brought her deep respect for the unconscious and for dreams to the Program. She invited all of us to honor and trust the world of dreams. She not only taught us how to welcome the dreams of the night, but also spoke about the “outer dreams” that she believed happened in the day when we really let ourselves see through a symbolic lens. Katy herself made life choices based on her dreams.

As a former potter, Katy led us in many creative exercises using clay, including opportunities to work with clay ourselves as a response to the images from Neolithic and Paleolithic times that we had been studying. She pointed out again and again that most of the figurines were very small, just the right size to be held in the human hand, suggesting a very intimate connection with the divine. Her teaching made the ancient figurines come alive, and helped us think not just about the figurines themselves, but also about the people who made them.

Katy’s respect for the creative process was profound, whether it manifested through dreams or through the arts. She had the mind of an artist and always brought us wonderful stories and unusual perspectives on whatever we were doing. She had a twinkle in her eye and a great sense of humor.

What brought me to women’s spirituality was reading. In some ways it seems strange, because so much of what happened was not based on books but on the experience of listening to my body, and trusting the truth of my own experience as a woman. Nonetheless, reading was what opened me to the ideas that were ultimately to become the foundation of the Women’s Well.

I am forever grateful to the women who wrote the first books on feminist spirituality and women’s spirituality. Their research, thinking, and writing changed my life (see, for example, Foremothers of the Women’s Spirituality Movement, Miriam Robbins Dexter and Vicki Noble, eds.).

I am forever grateful to the women who wrote the first books on feminist spirituality and women’s spirituality. Their research, thinking, and writing changed my life (see, for example, Foremothers of the Women’s Spirituality Movement, Miriam Robbins Dexter and Vicki Noble, eds.).The first book I read in this field was The Chalice and the Blade, by Riane Eisler, which called attention to the very masculine-dominated world we live in, and the serious consequences for the future of humanity and the planet of continuing on in this way. She offered examples from pre-history of societies organized in what she called a partnership model where caring, compassion, and the life-giving qualities of relatedness were highly valued.

In her book Riane referred to the research of a woman I had never heard of before, but whose work was to become a guidepost and inspiration for me and for many others in the women’s spirituality movement. Her name was Marija Gimbutas. She was an archaeologist who had researched the Neolithic cultures of what she came to call Old Europe (6500-3500 BCE). Here she found evidence of social structures where people were living peacefully in egalitarian ways with each other, and in harmony with the Earth. These cultures were highly evolved artistically, and the Mother principle was honored and revered as sacred.

How did I come across Riane Eisler’s book? In the late 80s several friends recommended it, saying, “You must read this, Anne. You will love it.” I was walking past a bookstore in Santa Barbara, CA, with a friend, and we decided to go in and see if they had it. We entered the bookstore and a man who worked there came right up to us and said, “Are you looking for The Chalice and The Blade?” He pointed to a big stack of books at the front of the store. We looked at each other and laughed. We were “in the magic,” as we came to call it. And it was not the last time that something like this would happen.

How did I come across Riane Eisler’s book? In the late 80s several friends recommended it, saying, “You must read this, Anne. You will love it.” I was walking past a bookstore in Santa Barbara, CA, with a friend, and we decided to go in and see if they had it. We entered the bookstore and a man who worked there came right up to us and said, “Are you looking for The Chalice and The Blade?” He pointed to a big stack of books at the front of the store. We looked at each other and laughed. We were “in the magic,” as we came to call it. And it was not the last time that something like this would happen.The next significant event for me was a trip to the former USSR in 1990, with a group of colleagues. We were going to be teaching Russian psychologists and therapists about Psychosynthesis, the spiritual psychology that we practiced in America. Disappointed not to be going to Moscow or St Petersburg, I was assigned to Lithuania, a country I knew nothing about.

We taught every afternoon, but in the mornings there was free time and my hosts asked me what kind of groups I wanted to meet in Vilnius. Nurses, politicians, musicians, teachers? I answered, “I would like to meet women.” “What kind of women?” they asked me. I answered, “Any kind of women.”

So the next day I was taken to the home of Lilija, a Lithuanian psychologist. There is much I can say about that morning, but at one point I was telling the group about women in America, and how we had been meeting in groups and talking to each other about our lives. I told them also about The Chalice and The Blade, and how the author was talking about ancient cultures which had honored women and the feminine. They were clearly very moved, and asked me if the book I was referring to had been written by Marija Gimbutas? I paused and said “No … but that name Marija Gimbutas seems familiar, and I think she was the archaeologist who researched those cultures I have been speaking to you about.” They said to me, did I know that Marija Gimbutas was Lithuanian, and that they were very proud of her! And also did I know that Lithuania was the last country in Europe to accept Christianity, and that for them the Earth is a goddess. The word for Earth was Žemė. The name of the goddess is Žemyna. I was stunned. Here was I in a country that I hadn’t wanted to come to, being given the next piece of a journey that I barely knew I was on.

I returned to the US with a wand traditionally carried at Easter in Lithuania that Lilija gave me to give to my mother. She showed me that it had the fronds for Christ at the top, and the flowers for the goddess all around the length.

One book led to another. I remember particularly China Galland’s Longing for Darkness: Tara and the Black Madonna. China Galland had been raised Catholic, and in the book she writes of her search for the darkness in Catholicism and particularly for the Dark Mother. Another very important book for me was Elinor Gadon’s The Once and Future Goddess, where she chronicles the history of goddess worship going back to the Paleolithic era (35000-9000 BCE). She writes of the patriarchal takeover, and what she calls the “taming” of the goddess and her powers, and then in the final section of the book, she illustrates with pictures and words the reemergence of goddess consciousness through the art and drama of women today.

One book led to another. I remember particularly China Galland’s Longing for Darkness: Tara and the Black Madonna. China Galland had been raised Catholic, and in the book she writes of her search for the darkness in Catholicism and particularly for the Dark Mother. Another very important book for me was Elinor Gadon’s The Once and Future Goddess, where she chronicles the history of goddess worship going back to the Paleolithic era (35000-9000 BCE). She writes of the patriarchal takeover, and what she calls the “taming” of the goddess and her powers, and then in the final section of the book, she illustrates with pictures and words the reemergence of goddess consciousness through the art and drama of women today. It all resonated so deeply with me, as if it were an articulation of a knowing I had always sensed, but never before had words or a context for. In the final section of her book, Elinor Gadon writes about the emergence of an Earth-based spirituality, the re-sacralization of sexuality, and the birth of Gaia consciousness - ecological wisdom for the renewal of life on this planet. As a peace activist and one who had studied and taught non-violence, reconciliation, and dialogue all through the 1980s, I was profoundly uplifted by her words.

It all resonated so deeply with me, as if it were an articulation of a knowing I had always sensed, but never before had words or a context for. In the final section of her book, Elinor Gadon writes about the emergence of an Earth-based spirituality, the re-sacralization of sexuality, and the birth of Gaia consciousness - ecological wisdom for the renewal of life on this planet. As a peace activist and one who had studied and taught non-violence, reconciliation, and dialogue all through the 1980s, I was profoundly uplifted by her words.I saved the chapter on Mary, in Elinor Gadon’s book, for the last. It was in the middle of the book but somehow I knew it would be the most important for me, and indeed it was. As I read, I realized that Mary, whom I had always loved, was a goddess and belonged to the long and ancient history of earlier goddesses. Within Christianity she had become demoted, and domesticated, and had been severed from her body, her sexuality, and her roots in the ancient goddess tradition of which she was an expression.

I was alone in an old house in the country when I read all this, and quite spontaneously I was flooded with joy. I began to weep and to dance. Suddenly a sense of ritual emerged, and I felt like I was in the presence of something that was Big, Beautiful, Powerful, and Female, and that I was being asked to open to it. I was being asked to say “Yes” to it. “Here I am.” And so I did.

In many ways, I feel like all the rest came out of this one moment, and the commitment I made that day.

Soon after, I learned that Elinor Gadon was starting a doctoral program in women’s spirituality at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. I decided to go for three months and try it out. I flew to the West coast, enrolled in three graduate courses, and had a room of my own for the first time since I left my family of origin at twenty-one. Creative ideas began to come to me like birds that had been hovering and wanted to land. It felt like they had just been waiting for me to stop taking care of everyone else, and listen for my own voice.

After three months of study, I decided to leave the program and to return home. My marriage needed attention, and I convinced myself that this was not the right graduate program for me. Whether that was true or not, I will never know. I was leaving the doctoral program, but I knew I was not leaving my newly found passion for women’s spirituality, nor the commitment I had made that day in the country to an expression of the divine feminine. I didn’t know how the choice I made then would express itself next, but I was open and listening for what it wanted from me.

Before I left California I bought a drum from a woman in Santa Cruz, who was making drums that she wanted to put in the hands of women. She told me that I should dedicate my drum to some quality or energy. I decided that I would dedicate my drum to freedom. I remember well returning to my home in Concord, MA, at a time when no one else was in the house, and walking through every room on all three floors beating my “freedom drum.”

Not long after my return home, a woman named Rose Thorne, whom I had known as a former director of the Interface Foundation, a center for holistic education in the Boston area, called me. She was searching, too. Her children were now in school, and she was considering divinity school, but had been disappointed that none of the schools she was considering had courses in meditation at that time. Someone had said to her, “Anne Yeomans has just come back from a very interesting program in California, you should go and talk to her.” She listened to me tell the story of what had happened in California, and said to me, “ We can start this here. We can start this here at Interface.” I knew immediately, when she said this, that this was the next step I had been looking for.

In the fall of 1993 Rose Thorne, Susan Chiatt, who was on the staff of Interface, and I began to plan the curriculum for a nine-month program in women’s spirituality which would begin the next fall. It would meet in a workshop form for one weekend a month from September to May. It would also have one or two evening meetings each month.

By then I had met Patricia Reis, who had written Through the Goddess: A Woman’s Way of Healing. She was a colleague of Marija Gimbutas, and as an artist had done drawings for Marija’s books. Patricia was the one person I had heard of on the East Coast who was writing about this material that I had become so passionate about. She lived in Maine, and with my copy of her book with my notes and under-linings throughout, I drove up to see her.

Soon after my visit, I called her and asked if she wanted to teach in the new program we were creating, and she responded with an enthusiastic Yes, and faxed me topics for three weekends. The first was to be called “Reclaiming Our Sacred History,” which she wanted to teach with Joan Marler, a friend and colleague of hers who was an independent scholar in California. Joan had worked closely with Marija Gimbutas, as had Patricia. Patricia also proposed a weekend on women’s body stories, and another on female sexuality. And so the program unfolded with Patricia Reis playing a major part as a teacher and facilitator, and Joan Marler coming each fall to teach the work of Marija Gimbutas. Olivia Hoblitzelle, Prajna Hallstrom, and Katy Szal would soon join us, each of them bringing her considerable talents, experience, and wisdom to the course.

In the fall of 1994, the first nine-month Women’s Spirituality Program at Interface began with a group of 20 women. This first year was the beginning of what would ultimately come to be called the Women’s Well. It brought us all so much: new learnings, profound healing, a community of extraordinary women, and ultimately the courage to be braver about what was most important to each of us.

Patricia Reis, co-founder and facilitator of the Women’s Well

In the early 1990s I attended a conference put on by Harvard University called “Learning from Women.” During the afternoon break, I saw Elinor Gadon whom I knew from my days in the San Francisco Bay Area. She introduced me to her friend, Anne Yeomans. The rest is, as they say, herstory. There were phone calls back and forth and a pivotal visit. Anne was on fire with her vision of a Women’s Spirituality Program. I had just published Through the Goddess: A Woman’s Way of Healing. It was dedicated to the Neolithic archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, my teacher, mentor, friend, matchmaker.

It is hard to describe those days of revelation. I had moved from California to Maine in 1986 and had a psychotherapy practice at Women to Women in Yarmouth. While in California, I had studied, worked, and traveled with Marija Gimbutas, and was part of a very large coterie of women who were drawn to her discoveries of the Neolithic Goddesses and their Old European cultures. Marija’s work had been taken up by so many women for so many different reasons: her discoveries gave evidence of a time that honored, revered, and worshipped female power in all its multiplicity; a whole movement of women’s spirituality was formed around these discoveries; the work of artists, musicians, and poets flourished; academically trained women took on the formidable task of reinforcing the evidence for a culture that did not have war at its center, where the female body and women’s wisdom was celebrated. As Anne Yeomans says, there was a great fluorescence of study, retreats, workshops, and books - so many books - on the impact of Marija’s discoveries on contemporary culture. This was the ground out of which the Women’s Spirituality Program was born.

It is hard to describe those days of revelation. I had moved from California to Maine in 1986 and had a psychotherapy practice at Women to Women in Yarmouth. While in California, I had studied, worked, and traveled with Marija Gimbutas, and was part of a very large coterie of women who were drawn to her discoveries of the Neolithic Goddesses and their Old European cultures. Marija’s work had been taken up by so many women for so many different reasons: her discoveries gave evidence of a time that honored, revered, and worshipped female power in all its multiplicity; a whole movement of women’s spirituality was formed around these discoveries; the work of artists, musicians, and poets flourished; academically trained women took on the formidable task of reinforcing the evidence for a culture that did not have war at its center, where the female body and women’s wisdom was celebrated. As Anne Yeomans says, there was a great fluorescence of study, retreats, workshops, and books - so many books - on the impact of Marija’s discoveries on contemporary culture. This was the ground out of which the Women’s Spirituality Program was born.

The creative force that was present at this birth was exhilarating. Planning meetings at Anne’s home in Concord were filled with intensity, possibility, and guidance. Doors opened for us, both outer and inner, wonderful women responded to our call for teachers, courageous and eager women responded to our call for participants in a nine-month-long intensive program called the Women’s Spirituality Program. The learning community of Interface was the first home for the program we developed. Later, after we moved out of Interface, we renamed our program the Women’s Well.

Each Fall a core group of facilitators would meet and craft the nine-month-long program. Anne would say I built the spine. I was eager to share what I had learned and was learning. I always began each new group with my slide show, "A Woman Artist’s Journey," a multi-layered story of my artistic process while pursuing an MFA at UCLA and simultaneously opening to goddess mythology and images which informed a kind of female initiation. My teaching drew on my creative interests, art, visual images, books, literature. Each topic was alive for me. Fathers and Daughters; Mothers and Daughters; Sexuality, Spirituality, and Creativity; Women, Work, and Money; Reclaiming the Erotic; the Body Story. This work was clearly not for sissies! It required a great deal of courage for each woman who had signed up for this program. We were all helped by the energy, devotion, and dare I say, hunger of each group that gathered every Fall.

Each weekend I taught, I came armed with a large roll of white butcher paper and a big bag of colored markers. My weekends were always a mix of story and image as women worked on large body drawings, or genealogical maps of how work and money flowed through the parental lineages. For instance, for the Sexuality, Spirituality, and Creativity weekend, I asked the group to look at the way these three aspects of our being have lived different and separate lives. I asked, “What have you been able to live into? To show to the world? What has had to remain hidden?” I asked them to divide a long piece of paper into the three parts and notice the places that were blocked, silenced, inhibited, and where there had been some overlap. Then I asked them to make a new drawing - an “as if” drawing - where their sexuality, spirituality, and creativity could be integrated and to see and feel what that would be like. Sometimes, like in Recovering Aphrodite, we brought large colorful scarves and moved our bodies in tune with what we were discovering.

We always built an altar in the center of our space, a beautiful collection of images and artifacts that reflected the work we were entering.

One time, after we moved from Interface, we rented a space in an old stone church. We were not given the room we had signed up for and instead were expected to do our weekend in the actual church with its sanctuary! The weekend was on Body and Soul! We protested and were given another gathering space that let us spread out. How deeply ironic that we were attempting to write a new body story for women in the very place where women’s bodies had been thought of as dangerous if not downright evil!

Synchronicities like this often happened as we did the work of reclaiming women’s spirituality. The focus and intention of a group of women bent on recovering their authenticity generated a powerful force field. Pain, fear, sorrow, and grief gave way to release, energy, old passions, and joy. We did not believe in doing a spiritual bypass on any of it. It was exhausting and exhilarating.

Part of the beauty of the work for me was the working principle that the leaders were also participants. I did my own body maps - the wounded body, the healed body - I did a map of my own story with work and money. As leaders, we stretched ourselves and did everything we were asking our group to do. After each weekend, we facilitators often debriefed over a sumptuous dinner of sushi.

Needless to say, this work was transformative for both leaders and participants. One of the beautiful experiences for me was how we, as facilitators, developed our deep trust in each other and in the unfolding process. There was fear sometimes, doubt, even anger, but ultimately, we grew to trust not only the process that we had initiated but also the women who had so courageously entered into the process with us.

Katy Szal, co-founder and facilitator of the Women’s Well

Katy Szal (1945-2004) was one of the three co-founders of the Women’s Well. She knew of the nine-month Women’s Spirituality Program, forerunner to the Women’s Well, from her long friendship with Anne Yeomans. The two had been neighbors in the coastal town of Westport, MA, where Katy lived, worked as a potter, gardened, and raised her daughter Amma. Anne came there with her family in the summers and joined Katy in many family and community events. At some point over the years they discovered that they had a shared interest in images and artifacts from pre-history, particularly those that honored women and the feminine.

During the years when both women had young families, Katy owned a successful pottery studio, Suntree Pottery, and made grey and blue pots and lamps that she sold at craft fairs around New England and in museum catalogues. She was a potter for twenty-five years, exhibiting in museums and galleries across the United States. During this time she also helped dismantle and reconstruct a post-and-beam house, originally built in 1680, and surrounded it with flowers and vegetable gardens. She was a master gardener and also a great cook.

During the years when both women had young families, Katy owned a successful pottery studio, Suntree Pottery, and made grey and blue pots and lamps that she sold at craft fairs around New England and in museum catalogues. She was a potter for twenty-five years, exhibiting in museums and galleries across the United States. During this time she also helped dismantle and reconstruct a post-and-beam house, originally built in 1680, and surrounded it with flowers and vegetable gardens. She was a master gardener and also a great cook.

In her forties, Katy initiated a major life change. She decided to focus on pursuing her lifelong interest in dreams and the guidance they offer. While still running her pottery business in Westport she embarked on a Master’s program in Counseling Psychology at the Pacifica Graduate Institute in Santa Barbara. After a summer program at the C.G. Jung Institute - Zurich, she made a leap of faith, closed the pottery studio, and moved to Zurich to pursue her dream of becoming a Jungian analyst. During that time, even though she was geographically far away, she followed the progress of the Women’s Spirituality Program closely, and sent Anne encouraging notes from Europe.

While in Switzerland studying Jungian psychology, she took numerous trips to the area of the Dordogne River in southern France, where she explored sites and caves where ancient artifacts had been discovered. She was determined to find the site where the Goddess of Laussel (20000 BCE) had been originally found. She knew this sculpture was discovered near the entrance to a cave near the Dordogne River where she and others believed ceremonies and rituals had been performed in ancient times. She spent several nights camping in that area at the time of the full moon, believing that our ancestors would have carved this image of the goddess in a place where the rising moon would have shone on it. She eventually identified the area where she thought it would most likely have been; she later took Anne there.

In December of 1994, Anne and Katy, pursuing their growing shared interest in the artifacts of pre-history, met up for a long weekend in Wiesbaden, Germany, to attend an art exhibit entitled “From The Language of the Goddess,” which explored the work of Marija Gimbutas. In the summer of 1995, they again traveled together in the Dordogne region of France where many of these ancient artifacts had been found.

After Katy completed her course work in Zurich, she returned to Massachusetts to write her thesis and was invited to join the Women’s Spirituality Program as a co-facilitator, starting in the fall of 1995. Katy brought to the Women’s Spirituality Program a lifelong passionate interest in archeology and the intimations it offers about the lives and priorities of our forbears. This interest had begun during her childhood in Arizona, where she had an uncanny knack for finding shards of pottery and spotting rock art and other evidence of people from earlier times.

After Katy completed her course work in Zurich, she returned to Massachusetts to write her thesis and was invited to join the Women’s Spirituality Program as a co-facilitator, starting in the fall of 1995. Katy brought to the Women’s Spirituality Program a lifelong passionate interest in archeology and the intimations it offers about the lives and priorities of our forbears. This interest had begun during her childhood in Arizona, where she had an uncanny knack for finding shards of pottery and spotting rock art and other evidence of people from earlier times.

Katy also brought her deep respect for the unconscious and for dreams to the Program. She invited all of us to honor and trust the world of dreams. She not only taught us how to welcome the dreams of the night, but also spoke about the “outer dreams” that she believed happened in the day when we really let ourselves see through a symbolic lens. Katy herself made life choices based on her dreams.

As a former potter, Katy led us in many creative exercises using clay, including opportunities to work with clay ourselves as a response to the images from Neolithic and Paleolithic times that we had been studying. She pointed out again and again that most of the figurines were very small, just the right size to be held in the human hand, suggesting a very intimate connection with the divine. Her teaching made the ancient figurines come alive, and helped us think not just about the figurines themselves, but also about the people who made them.

Katy’s respect for the creative process was profound, whether it manifested through dreams or through the arts. She had the mind of an artist and always brought us wonderful stories and unusual perspectives on whatever we were doing. She had a twinkle in her eye and a great sense of humor.

During the years when both women had young families, Katy owned a successful pottery studio, Suntree Pottery, and made grey and blue pots and lamps that she sold at craft fairs around New England and in museum catalogues. She was a potter for twenty-five years, exhibiting in museums and galleries across the United States. During this time she also helped dismantle and reconstruct a post-and-beam house, originally built in 1680, and surrounded it with flowers and vegetable gardens. She was a master gardener and also a great cook.

During the years when both women had young families, Katy owned a successful pottery studio, Suntree Pottery, and made grey and blue pots and lamps that she sold at craft fairs around New England and in museum catalogues. She was a potter for twenty-five years, exhibiting in museums and galleries across the United States. During this time she also helped dismantle and reconstruct a post-and-beam house, originally built in 1680, and surrounded it with flowers and vegetable gardens. She was a master gardener and also a great cook.In her forties, Katy initiated a major life change. She decided to focus on pursuing her lifelong interest in dreams and the guidance they offer. While still running her pottery business in Westport she embarked on a Master’s program in Counseling Psychology at the Pacifica Graduate Institute in Santa Barbara. After a summer program at the C.G. Jung Institute - Zurich, she made a leap of faith, closed the pottery studio, and moved to Zurich to pursue her dream of becoming a Jungian analyst. During that time, even though she was geographically far away, she followed the progress of the Women’s Spirituality Program closely, and sent Anne encouraging notes from Europe.

While in Switzerland studying Jungian psychology, she took numerous trips to the area of the Dordogne River in southern France, where she explored sites and caves where ancient artifacts had been discovered. She was determined to find the site where the Goddess of Laussel (20000 BCE) had been originally found. She knew this sculpture was discovered near the entrance to a cave near the Dordogne River where she and others believed ceremonies and rituals had been performed in ancient times. She spent several nights camping in that area at the time of the full moon, believing that our ancestors would have carved this image of the goddess in a place where the rising moon would have shone on it. She eventually identified the area where she thought it would most likely have been; she later took Anne there.

In December of 1994, Anne and Katy, pursuing their growing shared interest in the artifacts of pre-history, met up for a long weekend in Wiesbaden, Germany, to attend an art exhibit entitled “From The Language of the Goddess,” which explored the work of Marija Gimbutas. In the summer of 1995, they again traveled together in the Dordogne region of France where many of these ancient artifacts had been found.

After Katy completed her course work in Zurich, she returned to Massachusetts to write her thesis and was invited to join the Women’s Spirituality Program as a co-facilitator, starting in the fall of 1995. Katy brought to the Women’s Spirituality Program a lifelong passionate interest in archeology and the intimations it offers about the lives and priorities of our forbears. This interest had begun during her childhood in Arizona, where she had an uncanny knack for finding shards of pottery and spotting rock art and other evidence of people from earlier times.

After Katy completed her course work in Zurich, she returned to Massachusetts to write her thesis and was invited to join the Women’s Spirituality Program as a co-facilitator, starting in the fall of 1995. Katy brought to the Women’s Spirituality Program a lifelong passionate interest in archeology and the intimations it offers about the lives and priorities of our forbears. This interest had begun during her childhood in Arizona, where she had an uncanny knack for finding shards of pottery and spotting rock art and other evidence of people from earlier times.Katy also brought her deep respect for the unconscious and for dreams to the Program. She invited all of us to honor and trust the world of dreams. She not only taught us how to welcome the dreams of the night, but also spoke about the “outer dreams” that she believed happened in the day when we really let ourselves see through a symbolic lens. Katy herself made life choices based on her dreams.

As a former potter, Katy led us in many creative exercises using clay, including opportunities to work with clay ourselves as a response to the images from Neolithic and Paleolithic times that we had been studying. She pointed out again and again that most of the figurines were very small, just the right size to be held in the human hand, suggesting a very intimate connection with the divine. Her teaching made the ancient figurines come alive, and helped us think not just about the figurines themselves, but also about the people who made them.

Katy’s respect for the creative process was profound, whether it manifested through dreams or through the arts. She had the mind of an artist and always brought us wonderful stories and unusual perspectives on whatever we were doing. She had a twinkle in her eye and a great sense of humor.

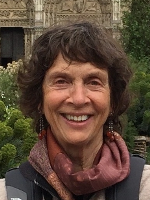

Left to right: Patricia, Anne, and Katy - three mask makers:

The content on this web site is a co-creation of a number of women, to whom we are extremely grateful. The image on our banner (top of page) depicts the interior of a Karanovo dish from Bulgaria, c. 4500 BC. Source: Figure 338, page 218, The Language of the Goddess, by Marija Gimbutas. Joan Marler, ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1989; used with permission.

If you wish to contact us, we have a gmail address. Our screen name is womenswellinfo.

Web hosting is provided by freehostia.com.

If you wish to contact us, we have a gmail address. Our screen name is womenswellinfo.

Web hosting is provided by freehostia.com.